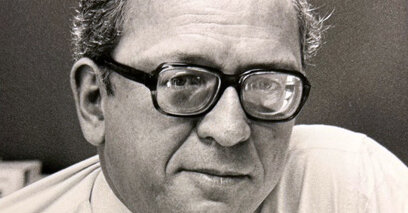

Richard J. Whalen, who in his diverse career wrote a best-selling biography of Joseph P. Kennedythe patriarch of the Democratic political dynasty, before joining Richard M. Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign as a speechwriter — but leaving before the election and writing a critical book about him — died July 18 in Yorktown Heights, N.Y. He was 87 old

His daughter, Laura Whalen Aram, said his death, in a nursing home, was caused by pneumonia.

Mr. Whalen is 27 years old and works at Fortune when the magazine published his 13,000-word profile of Joseph Kennedy in January 1963. His article described how he amassed a fortune and rose to become chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission and then, early in his time as United States ambassador to Britain, with war looming, “the publicly urged coexistence between Western democracy and Hitler’s Germany.”

But, the article continued, what he wanted more than money was political success for his children. “While making money,” wrote Mr. Whalen, “Kennedy managed to raise three attractive, persuasive children who easily approached leadership. Wealth facilitated their arrival; it’s not guaranteed.”

In early 1963, his eldest son, John, became president of the United States; his middle son, Robert, is the attorney general; and his youngest, Edward, was a senator from Massachusetts.

“In a way deeper than ordinary parental pride,” Mr. Whalen wrote, “their success is his.”

Soon Mr. Whalen had a dozen publishers, by his count, asking him to turn the article into a book. He received a $100,000 advance (about $1 million in today’s dollars) from the New American Library to write “The Founding Father: The Story of Joseph P. Kennedy” (1964), which preceded by decades other biographies of Mr. Kennedy like David Nasaw“The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy” (2012).

“What a surprise,” said Mr. Nasaw said in a phone interview, “he had almost none of the documentation that I and other Kennedy biographers had and he was able to get so much information about this man and get a sense of the conflicts, controversies and drives that motivated to him.”

“The Founding Father” spent 28 weeks on The New York Times’ hardcover best-seller list.

Mr. Whalen left Fortune in 1965 to become a writer in residence at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a bipartisan policy research think tank that at the time was affiliated with Georgetown University. An article he wrote for the center in 1967, about nuclear defense, caught the interest of Nixon, who asked him to be an adviser and spokesman as he sought the Republican presidential nomination.

But Mr. Whalen, a conservative, left the campaign shortly after Nixon’s nomination in August 1968. At the time, he attributed his departure to clashes with John Mitchell, the campaign manager, and other aides. But four years later, in his book “Catch the Falling Flag: A Republican’s Challenge to His Party,” Mr. Whalen shared his frustrations with Nixon, including his promise in March 1968 to end the Vietnam War, perhaps quickly, if President Lyndon B . Johnson didn’t finish it by the end of the year.

“This promise, hinting at a plan to fulfill it, splashed across the front pages and sent reporters and TV crews scurrying back to the Republican side of the New Hampshire campaign, eager for details,” he wrote. “Nothing. There was nothing behind the ‘promise’ other than Nixon’s instinct for extra sales effort when customers started walking away.”

Richard James Whalen was born on September 23, 1935, in Brooklyn. His father, George, was a textile executive, and his mother, Veronica (Southwick) Whalen, was a bookkeeper.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in 1957 from Queens College, where he studied English and political science, he was hired as a reporter at The Richmond News Leader in Virginia. While there he wrote about school desegregation and eventually became an editorial writer, working for James J. Kilpatrick, the paper’s editor, who was also a nationally known conservative columnist.

In 1960, Mr. Whalen for Time magazine, where, as a national affairs correspondent, he covered the civil rights movement. Shortly thereafter he moved to The Wall Street Journal as an editorial writer, but in 1962 he returned to Time Inc., where he became a staff writer on Fortune.

Later remembered Mr. Whalen that Henry Luce, the co-founder and editor in chief of Time Inc., commissioned him to write a profile of Joseph Kennedy, a longtime acquaintance of Mr. Luce. The Kennedys refused to cooperate with either the article or the book that followed.

“They’re not happy,” Joan (Giuffré) Whalen, Mr. Whalen’s wife, said by phone. But, he added, “We were told that Rose Kennedy enjoyed reading the book and grading it.”

The experiences of Mr. Whalen at the think tank and the Nixon campaign led him to other political work. He worked as a consultant and writer for William P. Rogers, Nixon’s secretary of state, from 1969 to 1970 and as a personal adviser to Ronald Reagan before and during his presidency.

In the late 1960s, Mr. Whalen started World Wide Information Resources, which provided his political, economic and foreign policy analyzes to subscribers, first by telex and then by fax and email. His lobbyist clients include Toyota Motor Sales USA, Toshiba America and the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

“I am a free trader who strongly believes that the US market is controlled by the consumer,” he told The Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1987 when asked about his lobbying for Japanese companies while the United States was there is a large trade deficit. “We’re pretty sure we’re going to hurt ourselves if we go down the protectionist route.”

In addition to his wife and daughter, Mr. Whalen is survived by his sons, R. Christopher and Michael; four grandchildren; and a brother, George.

The book of Mr. Whalen about President Nixon was published in May 1972, a month before the Watergate break-in, which became the scandal that led to his resignation two years later. While promoting the book, Mr. Whalen mocked Nixon as a monarch living in a “great court” and chastised him for failing to keep his promises as a conservative Republican.

“The difference between what your administration has done and proposed to do, and what the Humphrey administration will do, is not very significant,” he wrote in an opinion article for The New York Times, referring to his Democratic opponent. in the 1968 election, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey.

“I, too, know that you have a philosophy, which you once privately gave the name ‘conservative,'” he continued. “However, in public, you give your government the label ‘centrist,’ which often changes meaning as nonsense.”