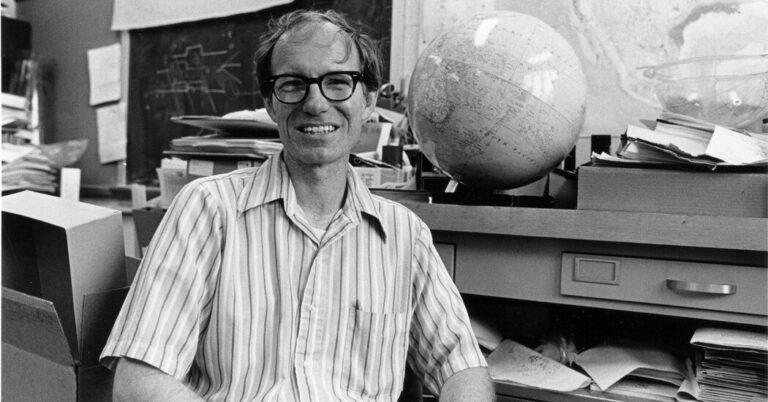

W. Jason Morgan, who in 1967 developed the theory of plate tectonics — a framework that revolutionized the study of earthquakes, volcanoes and the slow, steady shifting of continents throughout the earth’s mantle — has died on July 31 at his home in Natick, Mass. He was 87 years old.

His children, Jason and Michèle Morgan, confirmed the death.

The notion that the earth’s surface has moved was not new when Professor Morgan, who taught at Princeton University, first presented his theory at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington in April 1967. People had long noticed, for example, that the northeastern edge of South America seemed to match the notch along the west coast of Africa, and wondered if they sometimes fit together like puzzle pieces.

In the middle of the 20th century, researchers made significant steps forward in the study of the movement of the earth’s surface, including the discovery that stretches of sea floor are spreading. But the idea, called continental drift, remained highly contested in the 1960s, and no one had figured out a way to synthesize it all into a grand, testable framework.

Professor Morgan had originally planned to discuss underwater trenches at a meeting of the Geophysical Union. But after reading a paper about fracture zones — wide scars on the ocean floor that offer evidence of past distortions of the Earth’s surface — he changed his mind.

Looking at a map of several such zones in the Pacific Ocean, he realized that they were not random; they can be understood as the result of large plates colliding and separating as they slowly move across the globe.

He also postulated that the plates were rigid and well-shaped, whereas earlier theories argued that the continents circled the earth in a malleable mantle. That insight made it possible to measure plate motion in the past and predict it in the future.

With only a few weeks to go before his talk, Professor Morgan set aside his original subject and dived into his new speculation. He collected reams of data from expeditions to map the ocean floor, then built a computer program to test what he found against his hypothesis.

“Mom said she was working nonstop,” said her son Jason, himself a geophysicist. “And she’s a little nervous about what life will be like, married to an academic.”

Professor Morgan took only an outline to the podium, including handouts for the audience. He then turned his statement into a paper, which he published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in March 1968.

Meanwhile, a pair of researchers affiliated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Dan McKenzie and Robert Parker, published a paper in the journal Nature describing the same theory as Professor Morgan, although with different evidence.

While Professor McKenzie is sometimes credited with the discovery of plate tectonics, and while he, Professor Morgan and Xavier Le Pichonanother tectonics pioneer, shared the prestigious Japan Prize in 1990 in recognition of their work, Professor McKenzie said in a telephone interview that Professor Morgan “has priority” in taking credit for defining the theory.

The impact of plate tectonics is immediate. It offered a unified framework for research in the natural sciences, opening the door to new advances in seismology, volcanology and evolutionary biology.

“It all happened very, very quickly,” said Professor McKenzie, who later joined the faculty at the University of Cambridge, where he is now an emeritus professor. “In 1965, no one believed. By the end of 1967, it was all over.”

Academic and public acceptance of plate tectonics was so rapid and complete that within a decade it was standard fare in grade-school science textbooks. Some skeptics remained, but they too arrived at the moment when satellites and GPS data were able to confirm Professor Morgan’s theory without reservation.

“‘Paradigm shift’ is an overused phrase, but it is a paradigm shift,” John A. Tarduno, a professor of geophysics at the University of Rochester, said by phone.

William Jason Morgan was born on October 10, 1935, in Savannah, Ga., to William Morgan, who owned a hardware and dry goods store with his family, and Maxie Ponita (Donehoo) Morgan, a French teacher and a volunteer with the Girl Scouts of America.

He attended Georgia Tech, where he initially studied mechanical engineering with the goal of joining the family business. But midway through his studies he fell out of love with physics, switched majors (he graduated in 1955) and began looking for another career.

He spent two years in the Navy as an instructor at its Nuclear Power School, an experience that guided him toward graduate studies. He entered Princeton in 1959, received his doctorate in 1964 and remained at the university until his retirement in 2004.

She married Cary Goldschmidt in 1959. He died in 1991. In addition to their children, she is survived by six grandchildren.

Professor Morgan continued to make significant contributions after his paper on plate tectonics. In 1969 he and Professor McKenzie published a paper on the complex geophysics involved in the so-called triple junctionsplaces where three plates meet.

Later, he did important work on mantle plumes, fixed points hundreds of miles below the earth’s surface that occasionally send streams of molten rock upward — a phenomenon he argued resulted in in features such as the Hawaiian Islands.

Professor Morgan remained humble about his discovery, insisting that if he hadn’t done it, someone else would soon. Others were less hesitant to give him credit.

“The theory of plate tectonics that he published in 1968 was one of the major milestones of US science in the 20th century,” Anthony Dahlen, a former chairman of Princeton’s Department of Geosciences who died in 2007, said in a statement on 2003 after Professor Morgan. was selected to receive the National Medal of Science. “The scientific careers of a generation of geologists and geophysicists were founded on his landmark 1968 paper.”