An anticorruption crusader won a runoff election for Guatemala’s presidency on Sunday, delivering a stunning rebuke to the conservative political establishment in Central America’s most populous country.

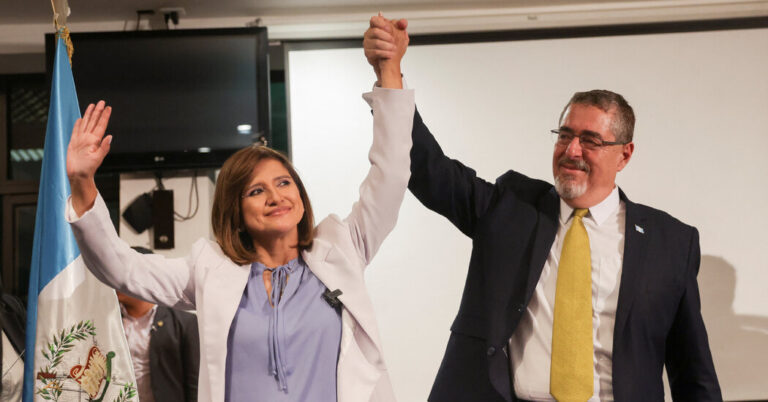

Bernardo Arévalo, a polyglot sociologist from an upstart party made up mostly of urban professionals, won 58 percent of the vote with 98 percent of the votes counted on Sunday, the electoral authority said. His opponent, Sandra Torres, a former first lady, got 37 percent.

Alejandro Giammattei, the current president, who is barred by law from seeking re-election, congratulated Mr. Arévalo and extended an invitation to arrange an “orderly” transfer of power.

The full official results are expected in the coming days.

Mr. Arévalo’s win was a watershed moment in Guatemala, one of Washington’s longtime allies in the region and a leading source of migration to the United States. Until he squeaked by in the runoff with a surprise showing in the first round in June, it was judicial leaders’ blocking of several other candidates seen as a threat to the country’s ruling elite that shaped the turbulent campaign.

Pushing back against such tactics, Mr. Arévalo has made the fight against graft the centerpiece of his campaign, focusing on investigating how Guatemala’s fragile democracy, repeatedly plagued by governments beset by scandal, has gone from spearheading anti-corruption strategies to stalling such efforts and forcing judges and prosecutors to flee the country.

Mr. Arévalo said on Sunday night that his government’s priority was to stop “political persecution against various types of government employees, and people who focus on corruption, human rights and the environment. “

One voter, Mauricio Armas, 47, said he voted for a candidate he believed in for the first time in decades. Mr. Arévalo and his party, Movimiento Semilla (Seed Movement), “seem like people who are not connected to criminal activity,” said Mr. Armas, a house painter and actor in the capital, Guatemala City.

Mr. Arévalo, 64, a moderate who criticizes leftist governments such as Nicaragua’s, is nevertheless viewed in Guatemala’s conservative political landscape as the most progressive candidate to come this far since democracy was restored to the country in 1985 after of more than three decades of military rule.

Because of its strong support from urban voters, Mr. Arévalo’s campaign contrasted with that of his rival, who focused more on crime and vowed to emulate Guatemala’s crackdown on gangs by Nayib Bukele, the conservative president of El Salvador. Ms. also highlighted Torres has championed social issues — opposing the legalization of abortion, gay marriage and marijuana — and has supported increasing food aid and cash payments to the poor.

“He’s promising security, doing what President Bukele did in El Salvador,” said one supporter, Aracely Gatica, 40, who sells hammocks at a market in downtown Guatemala City.

This is just the latest unsuccessful bid by Ms. Torres, 67, is the ex-wife of Álvaro Colom, who was president of Guatemala from 2008 to 2012. In 2011, she divorced Mr. Colom in an effort to overcome a law that prohibits a president’s relatives from running for office. (Mr. Colom died in January at age 71.)

Although he was barred from running in that contest, he was the runner-up in the two most recent presidential elections. After the latter, in 2019, he was jailed on charges of illicit campaign financing and spent time under house arrest. But a judge closed the case late last year, clearing the way for him to run.

Despite some obvious differences, Mr. Arévalo and Ms. Torres raised several issues in common. Both candidates, for example, called attention to Guatemala’s lack of decent infrastructure. Outside of Guatemala City, the country lacks paved roads, and Mr. Arévalo and Ms. Torres is building thousands of miles of new roads and improving existing roads. Both also promised to build Guatemala City’s first subway line.

However, Mr. Arévalo symbolizes a break with the established ways of doing politics in Guatemala. The race comes amid a crackdown by the current conservative administration on prosecutors and judges against corruption, as well as nonprofits and journalists like José Rubén Zamora, the publisher of a leading newspaper, who was sentenced in June to up to six years in prison.

While the president of Guatemala, the widely unpopular Mr. Giammattei, cannot seek re-election, concerns of a slide toward authoritarianism have intensified as he expands his power over the country’s institutions.

This institutional breakdown was on display on Sunday. Blanca Alfaro, a judge who helps lead the authority that oversees Guatemala’s elections, said she plans to resign in the coming days because of what she said were threats against her. Gabriel Aguilera, another judge at the electoral authority, said he also received threats.

In Guatemala City, firefighters said they responded to a fire caused by a small homemade bomb at a voting center in a middle-class neighborhood. While no one died and the fire was quickly extinguished, they said that they helped people who were showing signs of emotional stress. It was not immediately clear who was behind the bombing.

Before Mr. Arévalo’s appearance in the first round, the victory of an establishment standard-bearer seemed almost certain. But instead of benefiting the establishment’s preferred candidates, the disqualification of some contenders opened the way for Mr. Arévalo.

After he did it in the runoff, a top prosecutor whom the United States placed List Corrupt officials tried to stop Mr. Arévalo ran, but that move also backfired, prompting calls from Guatemalan political figures across the ideological spectrum to allow him to stay in the race.

Mr. Arévalo is the son of Juan José Arévalo, a former president who is still credited with creating Guatemala’s social security system and protecting free speech. After his father was forced into exile in the 1950s, Mr. Arévalo was born in Uruguay and grew up in Venezuela, Chile and Mexico before returning to Guatemala as a teenager. He was serving as a member of Congress when his party picked him this year as its candidate.

In recent days, the prosecutor who tried to stop Mr. Arévalo in the race, Rafael Curruchiche, revived his attempt to suspend Mr. Arévalo’s party. Citing what he claimed were irregularities in the process of gathering signatures to create the party, Mr. Curruchiche said he could suspend the party after Sunday’s election and issue arrest warrants for some of the its members.

Such a move could quickly undermine Mr. Arévalo’s ability to govern. Another warning sign was the high abstention rate in the runoff, with 45 percent of voters casting ballots.

But Ricardo Barrientos, a member of an alliance of groups in charge of the electoral process, said both the abstention rate and Mr. Arévalo’s wide margin of victory were expected, and in line with polling. “It’s an overwhelming majority” for Mr. Arévalo, Mr. Barrientos said.

Mr. Arévalo has pledged to reduce poverty in Guatemala, one of the most unequal countries in Latin America, through a major job creation program aimed at upgrading roads and other infrastructure. He also promised to increase agricultural production by providing low-interest loans to farmers.

Mr. Arévalo framed such measures as ways to prevent Guatemalans from leaving for the United States. A variety of factors stimulate migration, including limited economic opportunities, extortioncorruption in public officials and crime.

Mr. Arévalo has made tackling corruption and impunity the nucleus of his campaign. He distanced himself from rivals who sought to mirror Mr. Bukele in neighboring El Salvador, saying Guatemala’s security challenges are different in size and scope, with gang activity concentrated in certain parts of the country. Mr. Arévalo proposes hiring thousands of new police officers and upgrading security in prisons.

William López, 34, a teacher in Guatemala City who works in a call center, said he saw Mr. Arévalo and his party, Semilla, as “an opportunity for profound change, because they showed that they have no skeletons in their closet.”