Angelo Mozilo, a founder of Countrywide Financial who led that lender giant’s meteoric rise and then its collapse during the 2008 financial crisis, died Sunday. He was 84.

His death, in the Santa Barbara, Calif. area, was announced in a statement of the Mozilo Family Foundation, the family’s philanthropic organization. It has no specified cause.

The entire country was a key player in dealing with the housing crisis, when looser financial regulations allowed lenders to aggressively sell risky mortgage products to prospective homeowners, which contributes to a bubble in housing prices. That explosion, in 2008, when home values collapsed, led the US economy into a prolonged recession.

Mr. Mozilo, who is the son of a Bronx butcher and worked at Fordham University, became one of the most recognized executives linked to the crisis. From his humble beginnings, he built Countrywide into one of the nation’s largest mortgage lenders in the early 2000s. But he’s still not satisfied: He wants the company to achieve a 30 to 40 percent market share, more than what a lender has achieved.

The sale of complex mortgages to prospective homeowners with weaker financial profiles, a group often referred to as “subprime” borrowers, began to be pushed across the country. The loans required little or no money down and put many borrowers into homes they otherwise could not afford. Many of these loans, known as “no-doc” loans, do not require any income verification.

The go-go sales culture drove the company’s growth and profits but ultimately led to its downfall. As the housing market slumped and borrower defaults rose, Countrywide’s lending practices came under scrutiny from lawmakers, regulators and consumer advocates.

Financial pressures began to mount, and the company, based in Calabasas, Calif., west of Los Angeles, was acquired by Bank of America in 2008 at a fire sale price of $4 billion. But the purchase ended up costing Bank of America billions more in legal and other costs it inherited.

During that time, nearly 150 mortgage lenders failed, many of which were taken over by healthier institutions.

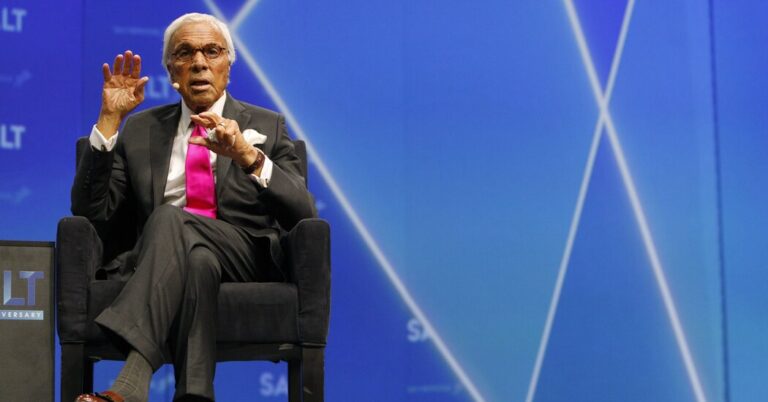

Mr. Mozilo, distinguished by his crisp suit and deep tan, continued to defend his company throughout the ordeal. “Nationwide is one of the greatest companies in the history of this country,” he told congressional investigators in September 2010, more than two years after Bank of America bought the company.

Regulators took a decidedly different view. In October 2010, Mr. Mozilo agreed to pay $22.5 million to settle federal charges that he misled investors about Countrywide’s risky loan portfolio. At the time, the settlement was the largest penalty ever imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission against a senior executive of a public company.

As part of the deal, Mr. Mozilo, which neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing, agreed to forfeit $45 million in “ill-gotten gains” to settle insider trading and other charges.

Angelo Robert Mozilo, the eldest of five children, was born on December 16, 1938, in the Bronx, where he grew up. When he was about 12 years old, he started helping his father, Ralph Mozilo, in his butcher shop, cleaning floors and cutting chicken, according to his member profile to the Horatio Alger Association.

By the time he was 14 he had his first job in the financial industry, working as a messenger boy for a mortgage company in Manhattan.

He was married to Phyllis (Ardese) Mozilo for over 50 years. He died in 2017. He is survived by their five children, Christy Mozilo Larsen and David, Elizabeth, Eric and Mark Mozilo; and 11 grandchildren.

Mr. Mozilo said he was unfairly portrayed as the villain of the housing crisis when many other lenders were involved, a view echoed by his family.

“Regardless of how people outside the industry may perceive this guy, insiders know what a formidable force he is,” Eric Mozilo said in a LinkedIn post on Tuesday.

“He was a great father and a legend in the mortgage industry,” she added in a phone call.

Mr. Mozilo and a partner, David Loeb, who died in 2003, started Countrywide in 1969 with $500,000. Over the course of several decades, the company grew from a conservative home lender, originally based in New York, to the largest mortgage lender in the United States. In 2007, it had 900 offices and $200 billion in assets and made $500 billion in loans that year.

In the early 1990s, after government data revealed that lenders were disproportionately turning down minority borrowers for home loans, Countrywide saw an untapped market and began offering more more loans to low-income and minority communities.

“When I first brought the loans to the office, they said: ‘You’re crazy, you’re crazy, don’t do this. There’s a reason we’re turning these people down,'” Mr. Mozilo later told a congressional commission. who investigates the crisis. Loan officers, he said, “have very static, inflexible rules.”

As he sees it, Countrywide is helping to break down racial and economic barriers to home ownership.

So he put staff through “sensitivity training” and hired more Black and Hispanic employees. Soon, one loan began to be approved throughout the country for every two applications reviewed, according to Mr. Mozilo. Previously, it approved one loan for every four applications. The new loans “happened,” he said.

But that performance didn’t last long. In 2006, Mr. Mozilo described some of the company’s riskier loans as “poison,” according to internal Countrywide emails released by the SEC in 2009. “In all my years in business, there has never been I have seen a more toxic” product, he wrote in an email.

More than a decade later, Mr. Mozilo spoke of how difficult that time was for his family, but he continued to defend his and his company’s legacy at a financial conference in Las Vegas.

“Of course it bothers me,” he said, according to a CNBC report in 2019. “It affected my reputation, it affected my family, it had a profound effect on my whole life. So I took care of it. Many years passed, and my husband died, and I became 80 years old, and now I don’t care. There are other things more important in life.”

Ben Protest contributed reporting.